Of Myth And Man: The Legacy Of Bob Marley – OpEd

By: Pambazuka News

September 21, 2012By David Cupples

With Jamaica having recently celebrated its Big 5-0 — fifty years of independence from Mother England — it’s natural to think of those things for which the tiny Caribbean island is famous. Fast sprinters and Olympic bobsledders. Patch-eyed pirates raiding the Spanish Main. Winter getaways to tropical beaches. A lyrical way of speaking, often imitated. Ganja and rum. For many it’s impossible to think of Jamaica without Bob Marley coming to mind.

A worldwide cult of followers worships Marley almost as a god-like figure, but in mainstream Western culture the man tends to be dismissed as a freaky pot-smoking dread who had some cool songs, and that’s about it. Certainly not someone to emulate. Not a man to be held up as a hero. No Mandela or Martin Luther King by any stretch of the imagination.

Well, hold on. On both a mythical and human level Bob Marley qualifies as a hero. Not a mere celebrity, but a true hero in the noblest sense of the word.

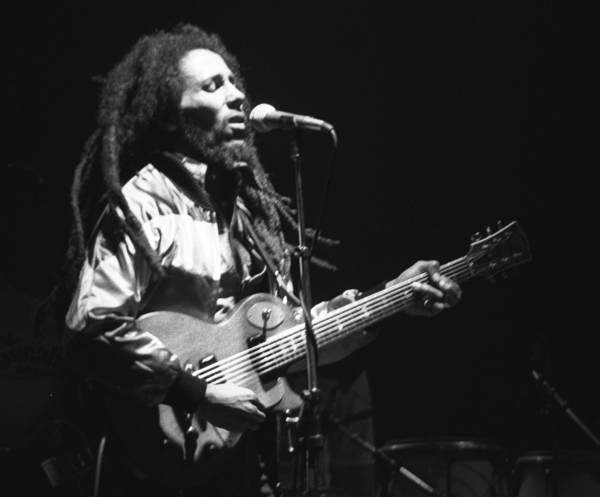

Marley in concert in 1980, Zurich, Switzerland

In the archetypal motif described by Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell, the hero typically comes from humble beginnings. Like Jesus, Mandela and King, Marley qualifies on that score. Born in a tiny shack in the back hills of Jamaica, Bob Marley grew up first as a barefoot country boy and later as a teenager on the mean streets of Kingston, ratchet knife in pocket and fists ready to fly. He never finished high school.

Next in the hero’s journey comes a call to adventure or action, often involving a Vision Quest or Walkabout. Seeking a way to deal with the hardships of ghetto living — as well as the sting of abandonment by his father and long periods of absence from his mother — Marley hiked not to the mountaintop but into the concrete jungle, to the heart of the inner city, where in the abyss of suffering and deprivation known as Back o’ Wall he encountered the teachings of Jah Rastafari. He’d always had music, but now his music acquired profound spiritual depth. Bob Marley, ghetto rudeboy, would become a messenger for Rasta, spreading the word of eternal life and the black man’s redemption through Haile Selassie I via the medium of his music. Marley had found his mission in life.

The next phase in the hero’s journey is initiation, consisting of one or many tests, like the labors of Hercules or the ordeals of Odysseus. For a penniless Third World ghetto-dweller to get his/Jah’s message out to the world was surely a Herculean chore. Guides (another archetypal motif in the hero’s story) like Joe Higgs, Seeco Patterson and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry tutored Bob and mates Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston (now Wailer) along the way, helping refine their vocal talents and — like Yoda with Luke Skywalker — completing their apprenticeship. But despite scoring a string of hits atop the Jamaican charts, the three ragamuffins could barely put food in their mouths, let alone shout Hosannas to the world. Down to their last few pounds, they marched into the London headquarters of Island Records and pleaded for money to make an album. Chris Blackwell sensed their integrity and slipped them a few thousand pounds; the three youths went home to Jamaica and within six months had crafted one of the great albums of all time, Catch A Fire. The messenger had found his voice.

The most exalted aspect of the hero’s saga is the sacrifice. Historical examples of the dying and resurgent god are many, among them Christ, Mithras and Dionysus. Psychologically, this represents the death of the individual ego as the hero is reborn a collective figure of hope and renewal—given over to a life for the good of all rather than himself (or herself; a woman can fulfill the archetypal role too). Jamaica in the 1970s was a hotbed of political strife, the two main political parties caught up in tribal war; many claimed the CIA was on the island stirring things up. Bob was caught in the middle and nearly paid with his life. In the end it was not a bullet that took him but cancer. Because of his religious beliefs he forswore the operation that might have saved his life and rather than rest he pushed himself to the brink to get his message out before his strength abandoned him. His rebirth was in his music, which continues to give hope and inspiration to millions, if not in the call to Rastafari, then in the ‘positive vibrations’ and message of love and unity his lyrics so brilliantly radiate.

So much for mythology — what about in real-life terms? Much of the world outside the West readily accepts Marley as a heroic figure. Ask Africans old enough to remember life under minority rule how the Jamaican’s songs gave inspiration to freedom fighters risking their lives to overthrow the tyrants. Ask South Africans who could not buy uncensored Marley records because the apartheid government feared the lyrics would incite rebellion. Ask Zimbabweans who were there in 1980 on Independence Day, when the Union Jack was taken down for the last time and the flag of the new nation raised—who was there to sing but Bob Marley and the Wailers?

Marley saw injustice all around and put it to music. He wisely perceived that the cruelest tyranny was hunger:

‘Them belly full but we hungry

A hungry mob is an angry mob (Them Belly Full)’

A hungry mob is an angry mob (Them Belly Full)’

He heard and reported the cries of the sufferahs:

‘Woman hold her head and cry

‘cuz her son had been shot down in the street and died

just because of the system (Johnny Was)’

‘cuz her son had been shot down in the street and died

just because of the system (Johnny Was)’

He warned of the repercussions that social and economic inequality would bring:

‘We’re gonna be burning and a-looting tonight (Burnin’ and Lootin’)’

Marley was an astute observer and social critic who let nothing pass. A favourite theme was the shit-stem (system) that made a hell of everyday existence:

‘Today they say that we are free

only to be chained in poverty

good god I think it’s illiteracy

it’s only a machine to make money’ (Slave Driver)

only to be chained in poverty

good god I think it’s illiteracy

it’s only a machine to make money’ (Slave Driver)

A machine powered by foreign influence and divide-and-rule tactics.

‘So they be bribing with their guns, spare parts and money’ (Ambush in the Night)

Marley wasn’t fooled:

‘Rasta don’t work for no CIA’ (Rat Race)

He spoke out against hard drugs–

‘All those drugs gonna make you slow

That’s not the music of the ghetto’ (Burnin’ and Lootin’)

That’s not the music of the ghetto’ (Burnin’ and Lootin’)

–and in favour of raising children with love and tenderness:

‘I heard my mother, she was praying in the night…

She said a child is born in this world

He needs protection

Lord guide and protect us

When we’re wrong please correct us’ (High Tide or Low Tide)

She said a child is born in this world

He needs protection

Lord guide and protect us

When we’re wrong please correct us’ (High Tide or Low Tide)

Marley sang of a revolution of the mind, echoing the deepest wisdom of humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers and existential philosophers like Sartre:

‘Emancipate yourself from mental slavery

none but ourselves can free our mind’ (Redemption Song)

none but ourselves can free our mind’ (Redemption Song)

He offered solace against the angst of modern times:

‘Have no fear for atomic energy

‘cause none of them can stop the time’ (Redemption Song)

‘cause none of them can stop the time’ (Redemption Song)

Marley’s guiding spiritual tenet was the doctrine of One Love, a reverence for the unity of all life:

‘In every man’s chest, there beats a heart’ (Zimbabwe)

A true revolutionary, he would turn the other cheek only so far:

‘So arm in arm, with arms,

we’ll fight this little struggle

cuz that’s the only way we can

overcome our little trouble’ (Zimbabwe)

we’ll fight this little struggle

cuz that’s the only way we can

overcome our little trouble’ (Zimbabwe)

Worldwide, Bob Marley’s lyrics may well have given inspiration and solace to as many as did King’s speeches, and he has come to symbolize resistance to oppression perhaps equally as much as the great civil rights leader. Africans seem to think so. In 1978, an African delegation to the UN presented Marley with the Third World Peace Medal — the former ghetto rudie formally recognized as one of the world’s great champions of freedom and human rights.

Carl Jung wrote of a corollary principle to the hero’s sacrifice — the archetypal impulse of underlings to kill the hero (much like the bloodlust of the sons of the primal horde to slay the clan patriarch, in Freud). Heroes have always been silenced by various methods, the most obvious being their death. One thinks of John Lennon, Malcolm X, Biko, Lumumba, Fred Hampton, Chris Hani, Che Guevara, Chico Mendes, Archbishop Romero and on and on and of course King himself.

When such figures aren’t murdered or imprisoned, they may be reviled, impugned, dismissed. Muhammad Ali was not widely revered in America until age and illness rendered him less threatening to white society. Similarly, King did not become a culture-wide icon until after his death, when the immense power of his presence was removed and only the brilliance of his words remained, rendering him palatable to the mainstream.

Bob Marley was easily dismissed as a dope smoker and profligate who fathered children willy-nilly with this woman and that, when in fact smoking ganja was part of Rastafarian religious belief and Marley as a rule was respectful to all his women; though not literally faithful to his wife Rita he cherished her all his days. Believing the creation of new life was sacred and beautiful he shunned birth control and took pains to ensure all his children were taken care of.

Writing Marley off as a wastrel — whether explicitly in words or implicitly through quiet shunning — is to view him through a Western prism. Of course, the real reason for dissing Marley, like King and Ali, was the threat he posed to the system. Even Mandela was viewed as a serious danger — he was officially designated a terrorist by Ronald Reagan (and Margaret Thatcher) and remained so designated until 2008.

Musically, despite a bright shining moment when Time declared Exodus the greatest album of the 20th Century, the presumed high authority Rolling Stone failed to include any Marley album not only in the top 10 but even the top 100 of its list of the 500 greatest albums. Fleetwood Mac at #26 and Exodus #169? If that’s not dismissal.

In the final analysis, there is little reason to argue over which hero stood the tallest. Just being mentioned in the same breath as Mandela and King is a supreme honor for anyone. Perhaps it is enough to say that Bob Marley was The Voice of the Third World and leave it at that. With much of Africa and the Caribbean having seen little development over the decades, feasting multinationals growing ever richer while the children continue to waste away… with Jamaica suffering the same poverty, lack of opportunity and violence seen thirty-five years ago… Africa plagued still by famine, disease and lack of infrastructure… American blacks faring proportionately far worse in the current economic crisis than their white counterparts, as if constituting a Third World nation within the ‘richest country on earth’ — with all this, we need to hear Marley’s message now more than ever.

David Cupples Ph. D is the author of Stir It Up: The CIA Targets Jamaica, Bob Marley and the Progressive Manley Government (a novel). He can be contacted via email atdavidcdusty@hotmail.com or through his Facebook Author page atwww.facebook.com/StirItUpCIAJamaica .